“As you know how we exhorted, and comforted, and charged every one of you, as a father does his own children, that you would walk worthy of God who calls you into His own kingdom and glory.” 1 Thessalonians 2:11-12 NKJV

Contemporary-Modern Models of Family Ministry

As the twentieth century faded into the twenty-first, God’s Spirit ignited a zeal in the hearts of His people to intentionally pass on the torch of faith to the next generation. This movement of God’s Spirit stirred the hearts of men, women, and church leaders worldwide to return to the biblical plan for family life thus igniting a reformation of family ministry across diverse denominations and theological traditions (Rienow, 2013, p. 201). Quite unlike the segmented-programmatic and educational-programmatic family ministry models, these newer contemporary models require far more than an addition of another program as a remedy to parental abdication of responsibility but much rather a reorientation of every ministry of the church to acknowledge, equip, and empower parents to engage their children in discipleship (Anthony, 2011, p. 173).*

*See part 1: “Family Ministry Throughout the Modern Era: Turn-of-the-Century & Beyond” on GFM’s website as linked below. Also see the author’s four part series: “Family Ministry Throughout Church History” linked below as well.

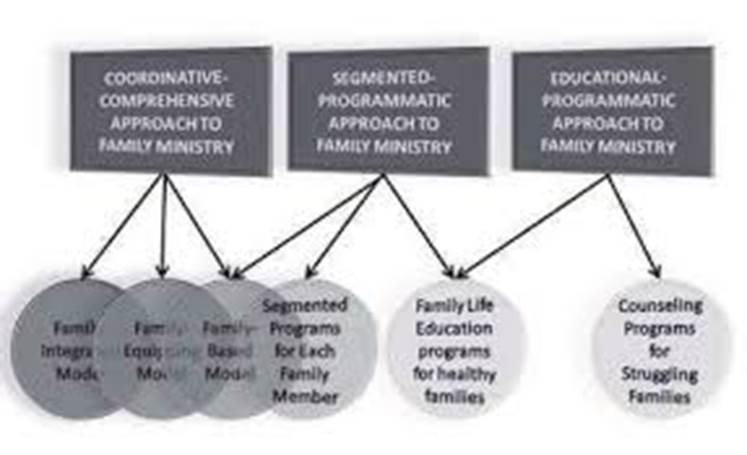

This complimentary relationship is affirmed, explains Steenburg and Jones, as the church should not try to do the work of the parents or for the parents but should intentionally partner with and equip the parents for their divinely ordained responsibility of this momentous task (Stinson, 2011, p. 159). Family ministry is therefore defined as the process of intentionally and persistently realigning a congregation’s proclamation and practices so that parents are acknowledged, trained, and held accountable as the persons primarily responsible for the discipleship of their children (Jones, 2009, p. 40). Within the context of this modern comprehensive-coordinative approach, the three primary models of cutting-edge family ministry that have arisen are the 1. Family-Based Ministry Model, 2. Family-Integrated Ministry Model, and the 3. Family-Equipping Ministry Model whose relationships to other models are illustrated in Figure 2 (Stinson, 2011, p .23, 159).

Figure 2

Envisioning the Relationship Between the Models of Ministry

Upon exploring these contemporary models, sage wisdom warns that family ministry is not the answer to the lack of vitality in a church or family dysfunction but is instead a mere vehicle that delivers the transforming power of the gospel (Stinson, 2011, p. 28). Neither are healthy families the goal and therefore family ministry an idol on par with the orgiastic shrines of Canaan or the pantheon of ancient Rome but the goal of biblical family life is none other than the glory of God alone that is demonstrated in practical experience through the gospel of Jesus Christ (Stinson, 2011, p. 28). Steenburg and Jones emphasize that it is faithfulness to this good news of creation, fall, and redemption vested in the Person and finished work of the Lord Jesus Christ that has throughout history been the beckoning call of God’s Spirit to parents to train their children so that God’s glory extends throughout the earth and resounds throughout eternity for the honor of His name (Stinson, 2011, p. 160).

Family-based ministry model. By adding activities and emphases to empower parents within age-segmented structures, the family-based ministry model seeks to merge a comprehensive-coordinative vision with the predominant segmented-programmatic model that remains prevalent in the majority of modern churches (Stinson, 2011, p. 25). What makes the practices of these churches different from the octopus-without-a-brain templates of the twentieth century, explains Jones (2009), is the focus of each ministry on empowering parental responsibility in the discipleship process and the inclusion of some intergenerational curriculum, activities, or events that foster interaction (p. 43). Reggie Joiner, leader of the Orange family ministry initiative, dubbed this approach as “supplemental family ministry” (Joiner as cited in Stinson, 2011, pp. 25-26). Timothy Paul Jones describes the family-based approach as a sunflower where each petal remains separate but all come together at the central disk just as church ministries remain separate but are united under the mission to empower parents and cultivate intergenerational interaction (Jones, 2009, p. 43). In this model, the job of the church is to keep the priority of family at the forefront of the congregation’s mission by empowering parents to raise godly children and transmit a legacy of faith (Anthony, 2011, p. 174).

Mark DeVries pioneered this approach in his 1994 book Family-Based Youth Ministry after he recognized that the real power for formulating faith was not in the youth program but in the families and the extended church family as “isolated youth programs cannot compete with the formative power of the family” unit (DeVries as cited in Stinson, 2011, p. 25). He further explains that merging this approach within the context of existing age-segmented structures is feasible because whereas most people “confuse the starting of a family-based youth ministry with a radical change in programming,” it is not about what the programming looks like but rather about “what you use the programming for” as we endeavor to point as much of it as possible toward “giving kids and adults excuses to interact together” (DeVries as cited in Baucham, 2007, pp. 193-194). Interestingly enough, proponents are quick to assert that the segmented-programmatic paradigm is neither faulty nor broken but merely in need of a rebalancing that empowers parents and emphasizes intergenerational relationships (Stinson, 2011, p. 26). Brandon Shields points out that there are

no pressing reasons for radical reorganization of restructuring of present ministry models. There is certainly no need for complete integration of age groups. What churches need to do is simply refocus existing age-appropriate groupings to partner intentionally with families in the discipleship process. (Shields as cited in Stinson, 2011, p. 26)

Even though the well-intended and very well-received family-based ministry model could be considered insufficient, it is indeed a very promising sign that there is a growing consensus regarding the centrality of parental responsibility in the discipleship process of the next generation (Baucham, 2007, p. 191).

Family-integrated ministry model. This contemporary approach is by far the most radical model as it represents a complete break from the “neo-traditional” segmented-programmatic paradigm as all or nearly all age-organized classes and events are eliminated as they are practices seen to be rooted in unbiblical, evolutionary, and secular thinking that usurps the jurisdictional authority of the home (Stinson, 2011, pp. 23-24). Family-integrated churches have no youth group, no children’s church, and no age-graded Sunday school classes thus liberating generations to worship and learn together with parents, especially fathers, shouldering the responsibility for the evangelism and discipleship of their children (Stinson, 2011, p. 23). Proponents describe the church “as a family of families” and in doing so are not redefining the essential nature of ecclesiology, as they are orthodox in their confession of faith, but are simply describing the functional structure of their evangelism and discipleship processes in and through the context of home and family (Baucham as cited in Anthony, 2011, p. 175).

In the latter decades of the twentieth century, Chicago-based church planter Henry Reyenga and Reb Bradley of Sacramento’s Hope Chapel were promoting age-integrated family discipleship in American churches (Stinson, 2011, p. 24). Others include Malan Nel who advocated a similar position among South African churches called inclusive-congregational ministry, Voddie Baucham, former pastor of Houston’s Grace Family Baptist Church, Doug Phillips, constitutional attorney and founder of Vision Forum Ministries whose retail division equipped families with manifold resources prior to its demise, Scott Brown of the National Center for Family Integrated Churches (nka Church & Family Life) who champions the sufficiency of Scripture applied to church and family life, and Paul Renfro, director of the Alliance for Church and Family Reformation (Jones, 2009, p. 42). Within the mid-Acts dispensational fellowship, Pastor Joel Finck’s annual Grace Family Conference, sponsored by Grace Bible Church of Tabor, South Dakota, gathers a large group of families from all sectors of the Grace Movement for encouragement in biblical family life and instruction in many of these principles.

Demographically, family-integrated churches are disproportionately comprised of homeschool families because this contemporary model of family ministry is based on many of the same foundational assumptions and principles that drive the home education movement (Baucham, 2007, p. 198). Timothy Paul Jones explains that even though these churches do not target homeschool families, they invariably attract and develop them because of the emphasis on the need for Christian education applied to every aspect of life (Anthony, 2011, p. 175). Baucham (2007) notes that this emphasis on Christian education as a key component of discipleship is one of the distinctives and guiding principles of the family-integrated church movement (pp. 198, 207).

The extreme nature of the family-integrated ministry model has been sharply criticized by the likes of Andreas Kostenberger and David Jones in God, Marriage, and Family: Rebuilding the Biblical Foundation as more purist in the application of its convictions (Kostenberger & Jones as cited in Stinson, 2011, p. 22). As a result of the epidemic of youth attrition which research has shown is partly due to the devastating effects of the lack of biblical and creation apologetics received in Sunday school, Ken Ham affirms that such drastic measures of total eradication of children’s and youth ministries need to at least be discussed (Ham, 2009, p. 46). The radical nature of doing so almost sounds blasphemous, says Ham (2009), because of the seemingly inseparable link between our concepts of “church” and “Sunday school” (p. 47). Although not an advocate of eradication, Ham (2009), along with his research team, diagnoses the absolute necessity to renovate youth and children’s ministry by overhauling these ineffective programs with apologetics curricula that overcome issues which undermine biblical authority in their thinking and subsequently drive them away from church (pp. 48-49).

In doing so, the complimentary relationship of church-home partnership is championed as parents, especially fathers, are equipped and challenged to not delegate their responsibility as the primary discipleship influence in their children’s lives. James H. Rutz, in his thought-provoking book, The Open Church: How to Bring Back the Exciting Life of the First Century, courageously analyzes the effectiveness of the Sunday school ritual (Ham, 2009, p. 50). Rutz explains that God’s plan for religious education is Dad, namely a millennia-old plan that has functioned like clockwork (Rutz as cited in Ham, 2009, p. 50). On the other hand, Rutz poignantly notes that, if Dad is not equipped to open his mouth at home through the weekly gathering of the local church, then Sunday school is your next best bet although programming Dad would be easier (Rutz as cited in Ham, 2009, p. 50). The family-integrated church emphasizes this approach but the family-equipping model strikes even more of a balance in the church-home partnership.

Family-equipping ministry model. This comprehensive-coordinative approach to family ministry transforms segmented-programmatic structures to co-champion the church’s ministry and the parent’s responsibility by reworking every children’s and youth program to resource, train, or directly involve parents thus holding them accountable as the primary faith trainers of the next generation (Stinson, 2011, p. 27). The family-equipping model, in many ways, represents a balanced middle route between the family-based model which merely adds programs to age-organized structures and the family-integrated model which drastically eliminates all age-organized structures from the life and ministry of a local church (Stinson, 2011, p. 27). Churches that consider themselves family-equipping may retain a youth or children’s minister, but their ministries do not continue to operate under the “neo-traditional” paradigm of the segmented-programmatic model of past generations (Anthony, 2011, p. 175).

Family-equipping ministry is a term coined by Timothy Paul Jones who alongside Randy Stinson developed its theoretical framework as they were redeveloping the curriculum in the School of Leadership and Church Ministry at The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in the early years of the twenty-first century (Jones, 2009, p. 44). In doing so, they discovered many other practitioners who were intent on co-championing the church-home relationship including Jay Strother at Brentwood Baptist Church in Tennessee, Brian Haynes at Kingsland Baptist Church in Texas, and Steve Wright at Providence Baptist Church in North Carolina (Jones, 2009, p. 44). Others like Ben Freudenberg advocate a similar model which he calls family-centered/church-supported and Michelle Anthony of Rock Harbor Church in southern California promotes family-empowered ministry (Jones, 2009, p. 44).

To envision the family-equipping model in action, Jones suggests imagining a river with large stones jutting out of the water’s surface (Anthony, 2011, p. 176). Either bank represents the church and home respectively whose coordinated effort prohibits the river from becoming a destructive deluge to the surrounding territory but rather ensures the constructive possibilities of a river (Anthony, 2011, p. 176). The large stones that guide and redirect the current of the river represent milestones in the life of a child that indicate the passing of significant thresholds of development which both church and home celebrate together (Anthony, 2011, p. 176).

In relating the contemporary models of family ministry together, Jones (2009) explains that none are exclusive of the others because each one is likely to overlap with others as they are implemented in the context of local church ministry (p. 45). While there are operational differences, each model shares the perennial truths of three biblical axioms: 1. God has called parents to take personal responsibility for the Christian formation of their children, 2. The generations need one another, and 3. Family ministry models must missionally-engage culture with the gospel along with the salt and light of the Christian biblical worldview (Anthony, 2011, pp. 178-179). Whereas the family-equipping model is viewed as the ideal, its principles are advantageous even when applied to segmented-programmatic and educational-programmatic contexts but they are especially useful to the quasi-comprehensive-coordinative model of family-based ministry and the purist family-integrated model (Stinson, 2011, p. 28).

Jones (2009) also confesses that his goal is not to convince readers of the superiority of any given model but rather his intention is to equip ministry leaders with knowledge that may help them discern which paradigm would best work in their congregation and a practical plan to implement the vision as every church is called to some form of intentional family ministry (pp. 45-46). Having said that, implementing a model of family ministry should not be driven by a form of ecclesial pragmatism but founded upon substantive theological and biblical considerations (Stinson, 2011, p. 27). “Here is the best news of all,” announces Richard Ross, professor of student ministries at Southern Seminary alongside colleagues Jones and Stinson, “because of God’s brilliance, that which is true is also that which ultimately works—because what is true brings glory to the triune God” and radiates the sovereign majesty of Christ “in and through families” (Stinson, 2011, p. 11).

Practical Application of Family Ministry

Reformation, revival, and revitalization of both church and family life are needed in every generation. God’s Spirit has ignited a movement of renewed emphasis on family ministry whose impact is reaping manifold dividends as churches are enriched and families equipped through the co-championing of the complimentary relationship of the church-home partnership. The family-equipping model of the comprehensive-coordinative approach to family ministry is therefore deemed the most biblically balanced model that churches would do well to proactively implement within the reoriented context of their twenty-first century ministry. Making this transition to a family-equipping ministry is beyond the scope of this research but practitioners like Jay Strother have laid out a comprehensive strategy that is workable in a variety of local church contexts (Stinson, 2011, p. 253). Having said that, the forthcoming recommended strategies would certainly be consistent with the family-equipping model, especially applicable to the other comprehensive-coordinative approaches, and of immense benefit to the “neo-traditional” segmented-programmatic ministry context.

To be continued…

Soli Deo Gloria!

References

Anthony, M. & Anthony, M., eds. (2011) A theology for family ministries. Nashville, TN: B&H Academic.

Baucham, Jr., V. (2007) Family driven faith: doing what it takes to raise sons and daughters who walk with God. Wheaton, IL: Crossway Books.

Ham, K. & Beemer, B. (2009) Already gone: why your kids will quit church and what you can do to stop it. Green Forest, AR: Master Books.

Jones, T. P., ed. (2009) Perspectives on family ministry: 3 Views. Nashville, TN: B&H Publishing Group.

Rienow, R. (2013) Limited church: unlimited kingdom – uniting church and family in the great commission. Nashville, TN: Randall House Publications. (2021 edition retitled, “Visionary Church: How Your Church Can Strengthen Families)

Stinson, R. & Jones, T. P., eds. (2011) Trained in the fear of God: family ministry in theological, historical, and practical perspective. Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Publications.